NOTE TO READERS: We are now on Twitter as @cachemaniacs. There’s a Twitter button over on the sidebar.

Hi again,

I started this series last year and got about halfway through it before getting side tracked. Since then, our Top 10 have changed a bit as we have been to some really cool places.

Here’s what we have so far.

#10 – Easy to Overlook Cache, Tucson, AZ

#9 – Nuke on a Mountain Cache, Sundance, WY

#8 – The Caves of the Door Bluff Headlands Cache, Door County, WI

#7 – Spooky Tunnel Cache, Kuhntown, PA

#6 – Trolls Cache, Livingston, MT

#5 – Dragoon Springs Geocache, Dragoon, AZ

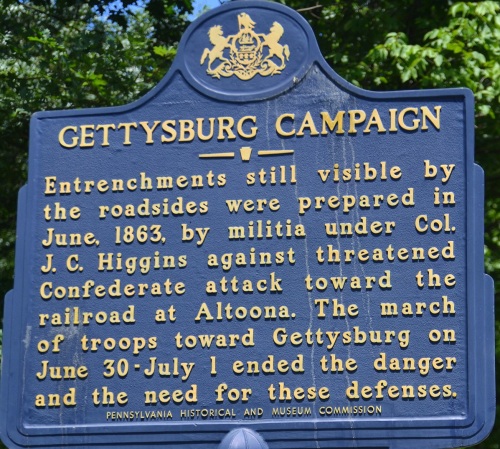

Trying to nail down the Top 10 is a moving target because as we travel around, we run into a lot of potential Top 10’s. To make the list, there has to be something extraordinary or unique about the geocache under consideration. It might distance, difficulty, terrain, location, history or just the surroundings. Our #4 cache fell into several of these but made the list because of the totally unexpected – and essentially unknown – events that happened here. From July 2012, the Civil War Entrenchments geocache.

June, 1863. Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia is on the move, heading north into Pennsylvania. Meanwhile, the Union Army is in Virginia, licking its wounds after the beating it took at Chancellorsville the month before. Lee’s army is riding high, full of confidence and taking the fight to the North, who seem unable to stop him. The coming Battle of Gettysburg isn’t on anybody’s radar yet. Lee wants to plunder the countryside, maybe capture a major city and force the Union into peace negotiations. At least, that’s the plan.

There was plenty to plunder in Pennsylvania including crops, horses, livestock, textiles, shoe factories, iron forges, warehouses and railroads. It was all undefended. There was no Union Army presence in the state, which was wide open to invasion.

A map of the battle area in the weeks leading up to Gettysburg. Most of the labels are self-explanatory. Letter B is the Snake Spring Gap and the location of the geocache. Letter C is Everett, where a cavalry skirmish occurred the week before Gettysburg. Letter D is McConnellsburg which was looted by Lee’s invasion force, along with Chambersburg. Total road distance from A-G is 155 miles.

A particularly lucrative target sat in the hills and valleys of central Pennsylvania – the railroad yards at Altoona, home of the Pennsylvania Railroad and the world famous Horseshoe Curve. The railroad was a major transportation link for the Union war effort and a target rich environment if there ever was one. Everything needed to fight a war could be found in the warehouses and marshalling yards of Altoona. Lee wanted to send a large raiding party to sack the town and wreck the train system, but first, he had to find a way over the steep, heavily wooded Allegheny Mountains. Initial reports had them undefended. In early June, he sent cavalry units under General John Imboden to recon a route.

Governor Andrew Curtin realized the gravity of the problem and also realized they would have to deal with it themselves. On June 13, 1863, telegrams went out to state and county leaders advising them of the situation and asking them to undertake emergency actions to deal with it. Colonel Jacob Higgins, a Union officer home on medical leave, was asked to lead the defenses in the mountains. He agreed and quickly went to work. The call went out for volunteers to build and man defensive positions against an impending Confederate invasion. Almost overnight, 1,500 men answered the call. They came from towns like Saxton, Roaring Spring and Morrison’s Cove. No records were kept. We have no idea who they were, what they did or where they went afterward. But we do know that for a few days in June 1863, they were on the front lines of the Civil War.

The trenchline at Snake Spring Gap. It is remarkably well preserved and can be followed for several hundred yards. At the end, it curves down slope to engage an enemy attack from the flank and prevent an end run. The terrain is very much like what it was in 1863. Steep, broken up and heavily wooded, it would have been almost impossible to mount an effective large-scale ground attack through it. The same thing can be found on the other side of the road, although it is much more overgrown and harder to follow.

The defenders’ biggest problem was time, which was as great an enemy as Lee’s Army. Higgins’ plan was to fortify four gaps where roads crossed over the mountains. These defiles were narrow, steep and heavily wooded. A few men could hold off many. One of those gaps was the Snake Spring Gap. Here, 500 men toiled non-stop for days to dig a formidable trenchline that extended for several hundred yards on both sides of the gap. Cannon were mounted in strong points next to the road. Attacking these positions would have been a daunting challenge. While the volunteers worked furiously on the defenses, militia cavalry went down the mountain to scout and delay the approaching rebel forces.

Meanwhile, Lee’s cavalry was pushing out in all directions for almost 100 miles. To the east, they were on the banks of the Susquehanna River and threatening the state capital at Harrisburg. To the west, they looted Chambersburg and McConnellsburg, then started towards Bedford and Altoona. In Everett (then called Bloody Run), they skirmished with militia cavalry, which showed up quite unexpectedly. When the rebel horse soldiers returned to McConnellsburg for more loot, they were run out of town by another militia cavalry unit. Confederate scouts got close enough to the barricades to report back that the gaps were heavily defended. These unforeseen developments were trouble for Lee’s plans. He wanted what was in Altoona, but the soft vulnerable target of several days ago was gone. Defenses had appeared seemingly overnight and Union cavalry was suddenly active in his area. Now headquartered in Chambersburg, Lee mulled his options.

An attackers view of the Snake Spring Gap. A strongpoint is visible ahead, effectively covering the entire narrow avenue of approach. From here, attackers would have probably been looking down the barrel of a six pounder loaded with double canister. The trenchline continues on both sides of the road for several hundred yards. At the top of the rise on the right, there are the remnants of another strongpoint anchoring that side and bracketing the road. The geocache is along that overgrown trenchline. The state historical marker is visible at the strongpoint.

The Union finalized his plans for him. On June 29 Lee’s scouts reported that the Union Army was in Frederick, MD moving north. He dropped the Altoona plan and turned southeast to meet the new threat. The rest, as they say, is history. On July 1, 1863, the two armies ran into each other at Gettysburg.

When the Battle of Gettysburg started, the mountain defenses were abandoned and everybody went home. There are many places in these Pennsylvania hills where you can find remnants of them, but the trenchline at Snake Spring Gap is the best preserved and most easily accessible.

One hundred years later on June 29, 1963, a state historical marker was placed here as a small bit of recognition for the unknown militia men who performed a brave and arduous task at a critical time.

As I have noted before, Pennsylvania is one big museum. All you have to do is drive down the road and you’ll find stuff. I’m a bit of a Civil War buff and grew up less than 50 miles away in Somerset County. I had never heard of any of this until I found this geocache online and decided to check it out. It is certainly off the beaten path. This important episode affected the course of the war but has been lost to history. The only reminders are some fading trenches, a state marker and a geocache, which comes in at #4.

If you ever want to check out the place, here is the geolocation:

N 40° 06.052 W 078° 23.345 . You can click on the coordinates to bring up a map.

Cheers …. Boris and Natasha

Aug 01, 2013 @ 00:07:38

Aug 29, 2013 @ 17:26:07

Jan 29, 2014 @ 23:35:41

May 10, 2014 @ 00:48:44

As a fellow central PA native, I was familiar with this story, but have never seen it written better than this!

Moreover, as Col. Jacob C. Higgins’ great-great-grandaughter, I thank you for this treasured piece of my family history. 🙂

May 10, 2014 @ 09:18:13

Thank you for your comments. I’m glad you enjoyed the write up. Central PA is one big museum, this being a classic example…Dan

Nov 25, 2014 @ 21:46:34

Boris and Natasha,

I really enjoyed your write up of the history that was made at this location. I enjoyed it so much that I added a link to it from my cache page. I hope your OK with that. I happened on this site while riding a bicycle from Altoona long before I cached. I have since met several descendants of Col J. Higgins.

Dec 04, 2014 @ 14:50:59

Glad you enjoyed it. Thanks for the positive comment and the link. If you send me your URL, I’ll put a link in my site. Thanks again … Dan the Webmaster aka Boris